How Faith Healers Fool You

Getting Drunk, High, and Hypnotized With Holy Koolaid | ⏱️ 13-minute read

Why do people let themselves get knocked to the floor at mass revivals? What is speaking in tongues? How are people miraculously cured of long-standing ailments — and why isn’t everyone who receives prayer from a faith healer?

I’ve been promising a video and written version of my conference presentation on this topic for a while. When my friend Thomas Westbrook invited me on his YouTube channel Holy Koolaid to collaborate on an exposé of faith healers, I leaped at the chance.

Learning the science behind the supernatural-looking phenomena I saw growing up in Charismatic Christianity was crucial to my healing from religious trauma. For years after I lost my faith, I was haunted by memories of what I’d been told was proof of the Holy Spirit — and therefore proof of God and, I believed, proof of hell.

I am thrilled to share what I’ve learned with a wider audience. My goal is not to mock people who undergo genuine mystical experiences, nor belittle the interpretations that may help give their lives meaning. My motive is to help people like my younger self who are desperate for evidence-based answers to faith-based confusion.

Watch my 10-minute video collaboration with Thomas, aka Holy Koolaid, above. If you enjoy his fast-paced and fun style of presenting helpful information, I hope you’ll subscribe to his YouTube channel and consider supporting him on Patreon.

If you prefer taking in information through writing, keep reading. I’ve added some of my original presentation slides throughout this piece and hyperlinks to my sources. The field of neurotheology is rapidly evolving as we continue learning about the mysteries of consciousness — or what believers call “soul.” I claim no certainties.

Now, imagine me onstage giving you permission to laugh or cry through the awkwardness of witnessing some bizarre-looking behavior. Some of you may find this disturbing, especially if you were religiously traumatized by coercive prayer, physical abuse, and failed healings. My sincere hope is that sharing this information will help free you of lingering doubt, fear, and self-hatred.

Without further ado, I present the written version of my most asked-for conference presentation:

Drunk, High, and Hypnotized: The Neurotheology of Mystical Experiences

I want to open this presentation by showing you the kind of Christianity I grew up in…

I was eight years old when my family joined this revival movement called the Toronto Blessing. We called the phenomena you just saw getting drunk on the Spirit. We also called it being slain by the Spirit and this, I was told, was what it looked like to be touched by God. This was what God did to you when he wanted to show you his love.

I desperately wanted to be loved by God. But God never touched me at any of the revivals my family and I went to. No matter how long I stood there with my arms outstretched, praying in earnest, I never felt the warm love of God that made people lose control of their bodies.

So, I learned to fake it. Whenever grown-ups put their hands on my head in prayer, I made a big show of shaking, crying, and falling to the floor just like I was supposed to. I was terrified I might go to hell because faking it bordered on blasphemy. Jesus said blasphemy of the Holy Spirit was the one sin that couldn’t be forgiven. I was also afraid that, if I didn’t fake it, everyone would know there was something wrong with me, something deeply sinful and broken that kept the Holy Spirit at bay.

“If God’s not touching you,” I was often told, “there is a sin in your life you haven’t repented for yet.”

I was twenty-one when I lost my faith. I didn’t want to be an atheist but after a series of heartbreaking betrayals (which I write about in my memoir Wayward), I finally admitted that I was unwilling to spend my life pretending to believe in a God who had never been real to me. But moving on from Christianity proved harder than I thought. I began having panic attacks, auditory hallucinations, and I was self-harming with fantasies of suicide. I now know that I was experiencing symptoms of Religious Trauma Syndrome (RTS), the PTSD-like condition some people experience after leaving their religion.

Years of therapy helped but I still felt haunted by certain aspects of my former faith. Specifically, I felt haunted by the manifestations I had once called being drunk on the Spirit. If it wasn’t God making people do all those crazy things, what was?

I didn’t think everyone had faked it. I thought something real had to have happened for at least some people. I couldn’t live with the lingering fear that God was indeed real and that I was now a hell-bound sinner for forsaking him. I needed to know what the manifestations of the Spirit were if not what people claimed them to be.

I am thrilled to show you what I discovered but first, a disclaimer: I am not an expert or a neuroscientist. I am simply a layperson who needed to understand what I’m about to share with you because, quite simply, it’s what helped me heal.

I’ve divided it into three parts: What, How, and Why. What was going on? How was it being done? Why were humans capable of these bizarre, altered states?

Also, why weren’t others, like me?

Part One: What?

What the hell was going on?

Well, my research showed it was not the Holy Spirit. Furthermore, what I called getting drunk on the Spirit was not unique to Christianity and was found in spiritual groups all over the world.

The !Kung and San people of southern Africa call it n/um, a healing state they get to through dance and chanting. The Indonesian-based movement Subud calls their spiritual practice latihan kejiwaan, a trance state they believe connects them to the divine. Chinese martial artists call it Qigong Deviation Syndrome and the Quakers and Shakers of England and Colonial America called it ecstatic dance or worship. Perhaps no other practice I’ve seen so closely compares to getting drunk on the Spirit than what Hindu yogis call Kundalini rising, or serpent awakening, which they believe is an energy release that leads to an expanded state of consciousness.

I put together a brief video showing the similarities between these altered states:

You may have noticed these different groups share many of the same symptoms: bodily shaking, rhythmic rocking, falling to the floor, writhing convulsions, crying or laughing uncontrollably, and glossolalia, or speaking in tongues. You may have also noticed the spiritual leader sometimes laying hands on the recipient, often by touching their forehead or what some call the third eye.

What’s going on, I learned, is that all of the people you just saw were undergoing a soberly-induced mystical experience. Many experiences might be described as mystical, such as lucid dreaming or having a near-death experience, or holding your newborn baby for the first time. For the purposes of this piece, I’ll be using this definition:

A mystical experience is a temporary altered state of consciousness that usually feels full of profound meaning.

Notice I said that the altered states you saw in the video were soberly-induced mystical experiences. This is because they can also be induced by non-sober means, such as ingesting psilocybin mushrooms or drinking the psychedelic tea known as ayahuasca. I’ll be focusing on soberly-induced mystical experiences, particularly those brought on by religious and spiritual means, but I’ll touch on other ones later.

My research showed that mystical experiences are indeed real — for some. Others like me may never be able to have them, not through sober means, and I’ll explore why. For now, let’s look closer at people who are capable of having a soberly-induced mystical experience. What is going on in their brain?

This question led me to the field of neurotheology. Bear with me through some science!

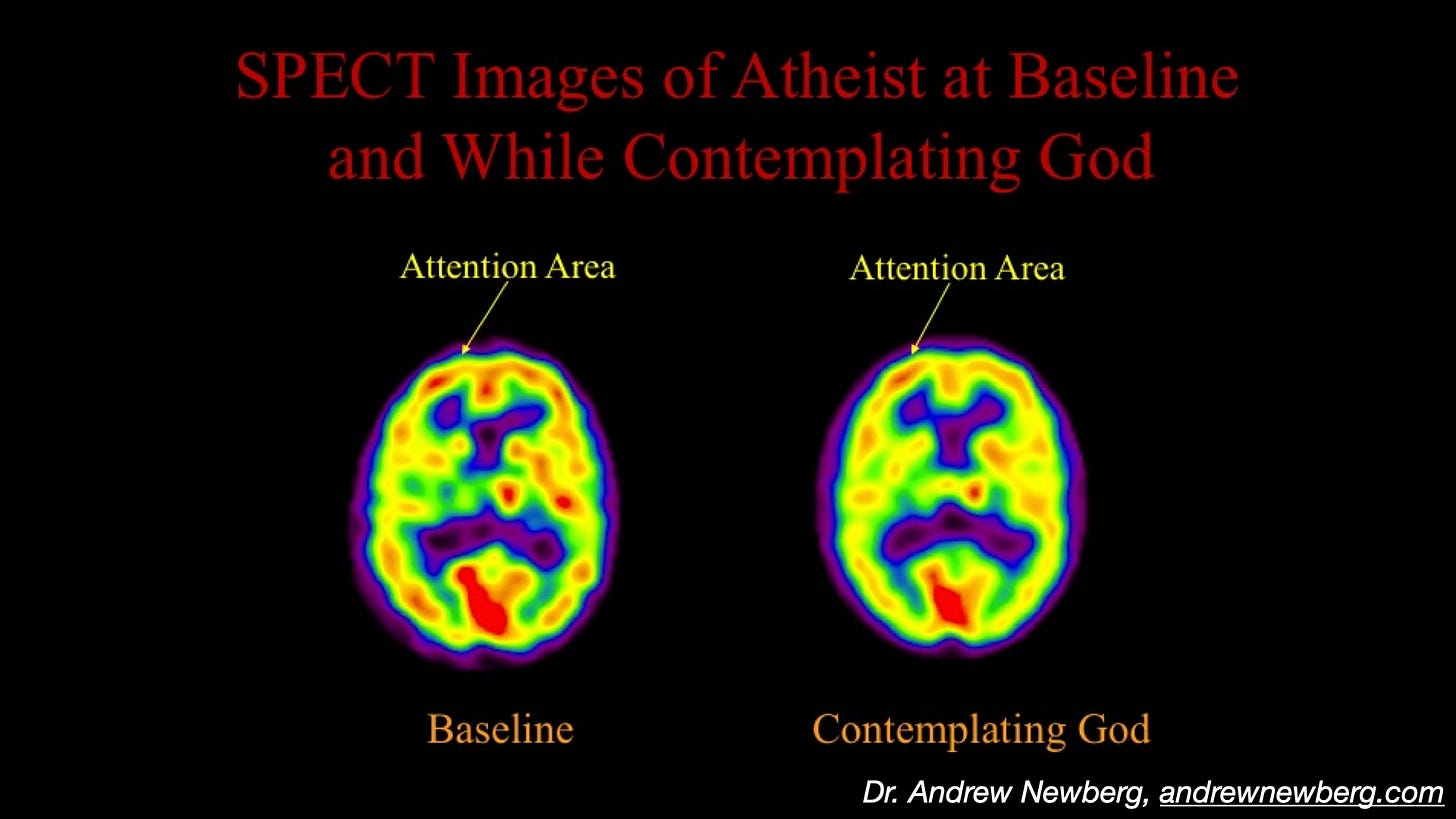

Neurotheology is the neuroscience of religious belief and spirituality. One of today’s leading neurotheologists is Dr. Andrew Newberg. Dr. Newberg has been studying the effect of belief on the human brain for decades. One of the insights he found is that different religious practices can have different effects on the brain.

For example, using SPECT imaging, Dr. Newberg found that the brains of meditating Buddhist monks showed increased activity in the frontal lobe, which is our concentration and attention area. That’s the red part of the brain you see lit up in this photo. Pentecostal Christians, however, showed decreased activity in the frontal lobe when they prayed in tongues.

The frontal lobe is partially responsible for language and voluntary movement. These images show that, compared to meditating Buddhist monks, Pentecostals engaged in glossolalia are in a lesser state of concentration — and therefore, have less control over their speech and motor functions. This may help explain the bodily shaking prevalent when people get drunk on the Spirit and undergo similar mystical experiences.

Researchers have observed glossolalia in other populations including Inuit tribes in the Arctic, the Saami people indigenous to Finland, and voodoo practitioners in Haiti. Some think glossolalia is best viewed as a dissociative state.

In other words, people speaking in glossolalia while undergoing a sober mystical experience are temporarily losing awareness of self. This may be why they’re not self-conscious when rolling around on the floor or crying and laughing uncontrollably.

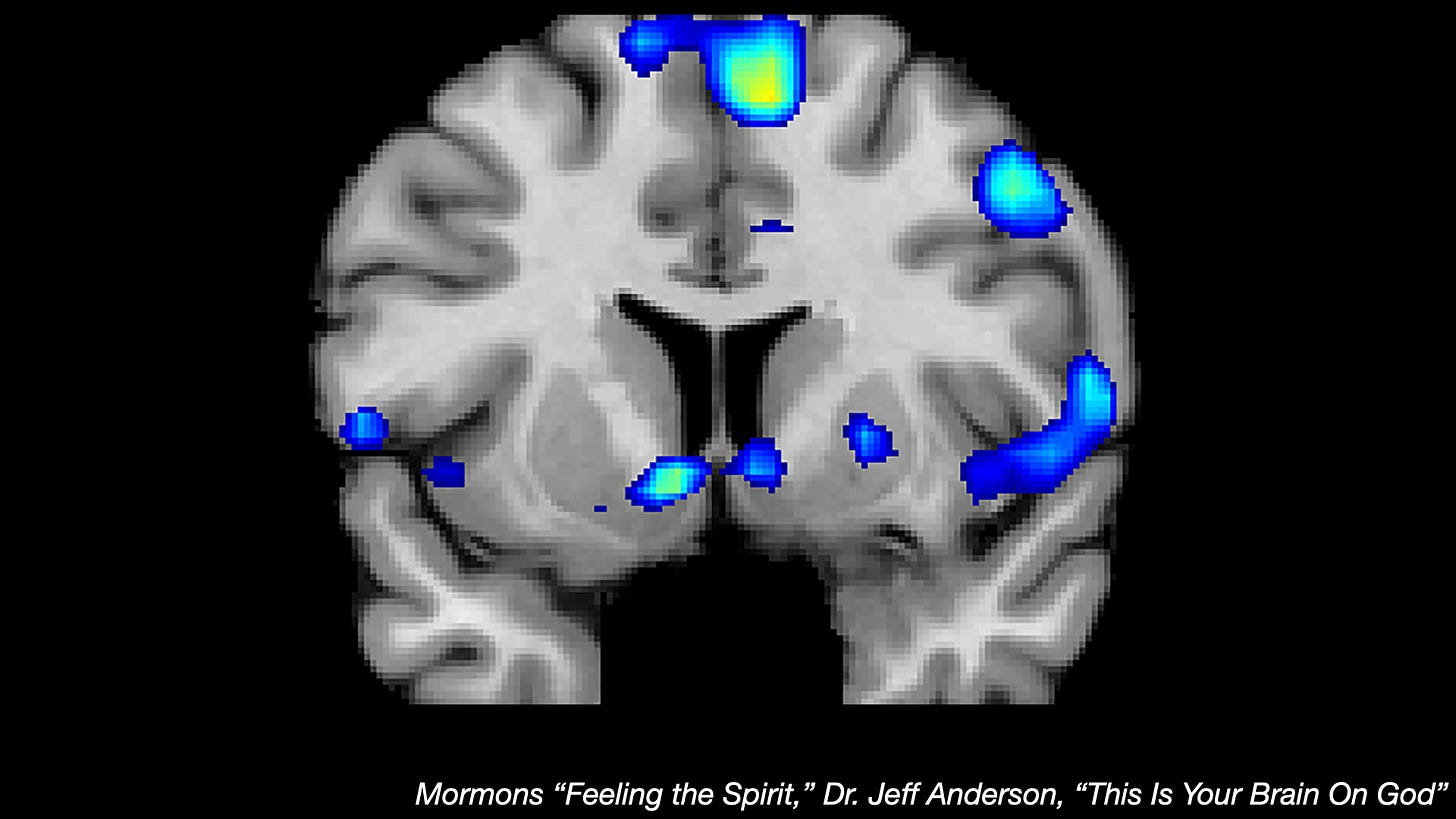

We also have data from neuroradiologist Dr. Jeff Anderson. Dr. Anderson conducted a study among Mormons using an fMRI machine. The participants were shown religious materials and asked whether they “felt the Spirit.” Most participants said they did at some point, reporting feelings like peace and physical sensations of warmth. Many were even moved to tears by the end of the scan.

This is what one participant’s brain looked like:

Their nucleus accumbens lit up.

The nucleus accumbens is the region of the brain that processes feelings of reward. Other things that light up the nucleus accumbens include sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll. One neurotransmitter facilitating these feelings of reward is dopamine. Dopamine plays an important role in mystical experiences and we’ll come back to it.

Now that we’ve established what these altered states are — mystical experiences — and neurologically validated their realness — at least for some — let’s move to part two: how.

Part Two: How?

How are people getting drunk on the Spirit and entering similar states like Kundalini rising? Is everyone faking it? Clearly not. Is it supernatural? I’m not inclined to think that, either. So what is causing people to have the very real symptoms that accompany these sorts of mystical experiences?

This question led me to a radio interview featuring an ex-Pentecostal pastor named Mark Haville. Haville wanted to come clean about how he once slayed people in the Spirit. The radio host asked him how it was that so many job-holding, tax-paying, average citizens let themselves be knocked to the floor and allegedly healed of illnesses at spiritual revivals. Haville’s answer was simple: hypnosis. He said people were falling because they were hypnotized, and being hypnotized makes us suggestible. It puts us in an altered state of consciousness.

I grew up believing that hypnosis might as well be witchcraft. If someone told the pastors of my youth that they were hypnotizing people, the accusation would have been met with vehement denial.

But Haville explained that hypnosis is largely misunderstood. A person can be hypnotized and still fully aware. Furthermore, spiritual leaders may not be hypnotizing people deliberately — and let’s give some benefit of the doubt, probably many aren’t. Regardless, the effects are often the same.

Now, a three-ingredient recipe for how to soberly induce a mystical experience.

1) Hypnosis

Our first ingredient is hypnosis. Haville says the best way to hypnotize a group at a spiritual revival is to first have a long period of praise and worship. Ideally, the music mirrors the cardiovascular system, when the rhythm pulses at the speed of a nice, relaxed heartbeat. Another integral part of hypnosis is the repetition of certain words and phrases by the worship leader or pastor. Music and phraseology help to hypnotize people, making us suggestible to mystical experiences.

I found clinical research backing up Haville’s claims. An HBO documentary called A Question of Miracles (now available on YouTube) introduced me to the work of late neurotheologist Dr. Michael Persinger. Dr. Persinger affirmed hypnosis is largely responsible for the mystical experiences of revival-goers. He presented the second ingredient at play in soberly inducing a mystical experience.

2) Group Dynamic Effect

The group dynamic effect might also be called herd mentality or peer pressure. It often occurs in large crowds. Dr. Persinger says that when thousands of people are gathered, particularly in a large space where they’re made to feel diminutive, their close proximity produces a special physiological arousal. This arousal gives people a sense of wholeness and unity, and we also see this outside of revivals at sports stadiums and music concerts.

Dr. Persinger says this arousal releases natural opiates in our brains. These opiates increase our hypnotizability. Once we’re in this ecstatic, expectant state — basically, once we’re high and hypnotized — the spiritual leader can orchestrate mystical experiences. As they begin giving their message, they’re full of emotion and imagery. These images, Dr. Persinger says — such as cleansing fire pouring from heaven or a healing river flowing through the congregation — “…take on tremendous personal value because of the elevation of the opiates…and then you see all the features of an opiate release. You get the smiles, a very mild glow, very much like a drunken state.”

What’s something else opiates do? Opiates dull our pain.

I grew up watching thousands of people get drunk on the Spirit and claim to be healed of everything from arthritis to cancer. Some walked for the first time in years or danced down the aisle weeping with gratitude. This is because hypnosis can temporarily dull our pain receptors. This is why some women use hypnosis techniques in childbirth and why people hypnotized at a revival can genuinely believe themselves divinely healed. They truly may not be experiencing any pain.

3) Placebo Effect

The last ingredient in our recipe for soberly inducing a mystical experience is the placebo effect. Basically, our expectation or desire to have a mystical experience can sometimes be enough to bring one on — especially in combination with hypnosis and the group dynamic effect.

Dr. Neil Abbot is a researcher who conducted a study on volunteers suffering from chronic pain. He told them to lie in a room for half an hour while an energy healer worked on them from a nearby cubicle. Those who believed in the power of healers reported a significant reduction in pain. They also described balls of light and powerful physical sensations. But there was a catch: In half the cases, a healer was present performing a full ritual; for the other half, the cubicle was empty. The results were the same, with or without a healer.

Dr. Persinger likens this experiment to the placebo effect of revival-goers getting drunk on the Spirit. Many of them come hoping for healings and spiritual breakthroughs. Because of their desire and belief, they are more inclined to actually experience these.

A Moment of Acknowledgement

Before we move to part three, I want to acknowledge that these explanations may sound offensive to you, especially if you have undergone a genuine mystical experience. No one wants to think they were simply hypnotized and it worked because of their wishful thinking. I don’t mean to downplay or trivialize the importance of your experience. Also, we might all be susceptible to the placebo effect and hypnosis under certain circumstances, particularly when our confirmation bias is at play.

Again, my intention is not to belittle mystical experiences. I aim to demystify them so that people suffering from religious trauma might be assuaged of lingering supernatural fears.

Part Three: Why?

Why are some people capable of having a soberly-induced mystical experience? Why aren’t others? Why are we able to be hypnotized, or enter trance states and do things like speak in tongues?

Asking why humans can have mystical experiences that alter our consciousness might be like asking why we have consciousness at all.

What is consciousness? We don’t yet have a solid, agreed-upon answer. To some, consciousness is synonymous with the soul, or thought of as a cosmic energy playing on the hardware of our brains. To others, consciousness is the product of our brains — nothing from outside ourselves but generated from within, a fascinating result of our physicality. When our brain dies, does our consciousness? Why do we dream? Why do we have deja vu and out-of-body experiences?

I’m a person who can ask why all day long. The more satisfying question I now love to ask is how. Sometimes, asking how can lead us to the why. Often, it leads me to this unsatisfactory answer: We don’t know.

If this frustrates you, I share your pain.

What is evident is that faith can have an undeniable effect on the human brain. Your brain during a mystical experience lights up the same areas as drug and alcohol intoxication, or gambling, or sex with a new partner. Why? Maybe because, like these other examples, mystical experiences just feel good. But are they accessible to all?

Genetics

Who is capable of having a soberly-induced mystical experience and why isn’t everyone, like me? Some studies suggest that the expression of a certain gene called VMAT2 is partly responsible.

VMAT2 was dubbed “the God gene” by geneticist Dene Hamer, who also authored a book by the same name. VMAT2 affects our monoamine levels, which affect our levels of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. Put simply, “the God gene” can affect our feel-good hormones.

Hamer hypothesizes that these hormones play an important role in regulating brain activity associated with mystic belief. Separate studies of twins show a 40-50% genetic component to whether or not one believes in God, even among twins separated at birth. Yet another study verifies that genes may account for up to 50% of our religiosity — and deductively, our lack thereof.

Studies like this are often flawed. Most rely on self-reporting, which is rather immeasurable. It may be oversimplifying to suggest there is one gene responsible for your core beliefs, and therefore the beliefs of entire nations and cultures. But when we have little reason to suspect brain scan images are lying, or the genotyping results of DNA, self-reports become easier to verify.

Just as brain scans confirm certain activity in the brains of spiritual people, other studies verify the different neural wiring of nonbelievers.

This image shows the brain of a long-term meditator who is also an atheist. Neurotheologist Dr. Andrew Newberg said this man’s frontal lobe did not light up when asked to meditate on God. You’ll notice a lot less red in his attention area than the Buddhist monks had when they were meditating. The implication, Dr. Newberg says, is that, “…the individual was not able to activate structures… [when] focusing on a concept he did not believe in.”

Other studies suggest atheists may have a larger hippocampus and less dopamine in their brains.

Remember I said that dopamine plays a significant role in mystical experiences? Some neuroscientists think a variance in dopaminergic genes is responsible for a person’s ability to speak in tongues. The results of another study suggest that highly hypnotizable people have a more effective frontolimbic attentional system, further suggesting the involvement of dopamine in hypnotizability.

Maybe atheists and others don’t have the genetic expression allowing us to enter soberly-induced trance states, therefore not allowing us to have soberly-induced mystical experiences.

Then there’s this take…

Some researchers suggest that atheism evolved from mutated genes. Atheism has been linked to other genetic abnormalities, like autism, asymmetry, and left-handedness. The data here is loose but it does make sense that atheism could be rare among humans because not going along with a spiritual program means not going along with a cultural program, which — evolutionally — means a risk of ostracism and therefore a lesser chance of survival.

It may be that evolution favored obedient believers more than non-believing contrarians. Maybe it was our more spiritual ancestors, who perhaps had more mystical experiences, who were primed toward belief because of certain genetic traits. Their faith may have given them a greater will to survive and the social cooperation incentives necessary to get through cataclysmic environmental changes. Perhaps this resulted in more spiritually-prone offspring, as people without a genetic propensity for faith may have died out.

Theories of this sort of natural selection don’t seem far-fetched to me. From neurosurgeons to anthropologists, numerous experts agree that spiritual capacities could have been a cognitive development necessary for survival.

As a result, some people’s dopamine systems make them more susceptible to being hypnotized or entering trance states. Others, like me, seem to have a harder time letting go of our frontal lobe activity — the part of the brain responsible for staying in control. This means we have a harder time achieving soberly-induced mystical experiences.

Far from it being our fault, it may simply be our genetic inheritance.

In Conclusion

Understanding the science behind mystical experiences is what gave me peace about never having any. Not through sober, spiritual means, anyway. As I said earlier, mystical experiences can also be attained through non-sober means.

LSD, magic mushrooms, and ayahuasca don’t care what you believe. I’m personally so grateful to psychedelics for allowing feelings of transcendence and unity for all — not just those more hardwired toward faith. There is no faith required to experience the effects of dropping acid. While I am not encouraging illegal activity, I do encourage you to learn about clinical studies being done with psychedelics.

The findings of neurotheology helped me see that I was never left out by God. What I’d called getting drunk on the Spirit was likely nothing more than a neurological cocktail of feel-good serotonin, thrilling dopamine, and blissful hits of oxytocin. This is the meld that leaves people feeling lost in the infinite love of the Divine.

One really can get high on Jesus. One really can get drunk on the Spirit. One really can become something of a spiritual addict as their brain craves the opiate release that keeps them coming back for more. Neurologically, the mystical experiences of revivals are not unlike a mass drug outpouring and just like with psychedelics, there can be good trips and bad trips. All might be considered healing journeys.

As for the bizarre bodily symptoms like shaking, rolling around on the floor, and sobbing or giggling uncontrollably? If you’ve ever had a non-soberly induced mystical experience, such as tripping acid or mushrooms, you may have noticed similar behavior under those circumstances. Mystical experiences, whether soberly-induced, plant-induced, or pharmaceutically-induced, share some odd-looking traits. On the outside, it can look like lunacy, with visual hallucinations, weird noises, and bodily movements. On the inside, genuine transformation can be taking place.

Neurotheology helped me see that there was never a sin in my life that kept God at bay. It wasn’t because I didn’t have enough faith that God never touched me. Or you. While we still have much to learn about the neuroscience of what we call spirituality, everything I’ve learned has assuaged me of any supernatural fears. I don’t think there is anything super-natural. I think what we call the supernatural is just a lazy and arrogant way to avoid saying, We don’t know yet. And the yet is my favorite part.

Once more, it is my deepest hope that sharing this information with you helps to assuage you of any lingering supernatural fears, doubts, and self-hatred. If you could use faith-friendly or secular resources to help you heal from religious trauma, please visit DaretoDoubt.org.

I’m Alice Greczyn, an author and speaker. This newsletter is free because I think helpful information should be free as much as possible. Please subscribe, and if you’d like to donate to my costs (news subscriptions, image licensing, audio recording, etc.), I’d surely appreciate it. Thank you.

Great read, Alice! I'm one who has never experienced a mystical experience of any sort; not one I can remember, anyway. Should I add that to my bucket list? I'm quite certain it could not be soberly induced. Your conclusion is not shocking to me, but I am surprised to learn that many people are not faking these experiences. Glossolalia has always seemed like something people have to be faking. I'm surprised to read that most are not. However, I'm not surprised, in the least, that the explanation for Glossolalia and mystical experiences is not that there is a God. I sure hope anyone suffering from RTS or from the confusion as to why God has not revealed himself reads this and gains the comfort you received from researching and writing it.